Türkiye is moving swiftly to cement a place in Southeast Asia’s security landscape, attaining defence exports with several high-level visits.

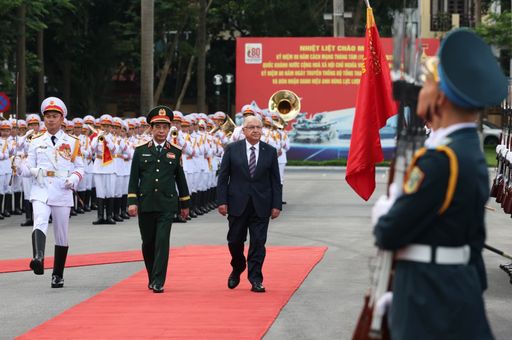

Ankara’s latest initiative came in Hanoi, where Defence Minister Yasar Guler held talks aimed at strengthening cooperation with Vietnam—an engagement Vietnamese leaders cast as a practical step to implement a newly signed defence accord.

For regional governments hedging between Washington and Beijing, Türkiye’s pitch is straightforward: proven hardware, flexible terms, and co-production that builds local industry—without political strings.

“Unlike other powers, Türkiye carries no historical baggage in Southeast Asia,” Associate Professor Murat Yas from Marmara University in Istanbul tells TRTWorld,

“It did not intervene in the Vietnam War and has no colonial legacy here. That clean slate lets Ankara present itself not as a patron demanding alignment, but as a partner offering technology, training, and industrial cooperation on terms respectful of sovereignty.”

Southeast Asia deals

In the region’s most striking vote of confidence, Indonesia signed for 48 KAAN fifth-generation fighter jets, Türkiye’s first export of its indigenous combat aircraft.

Jakarta billed the deal as a pillar of its long-term modernisation, with provisions for technology transfer and local workshare; for Ankara, it marked a breakout in the Indo-Pacific market.

Altay Atli, a scholar of Türkiye–Asia ties at Koc University in Istanbul, says the moment fits a broader strategic pattern. “Türkiye is a NATO member and an EU candidate, but it also pursues strategic autonomy—engaging East and West while avoiding forced choices,” he tells TRTWorld. “That language resonates in Southeast Asia, where states want options, not alignments.”

Malaysia has started operating Turkish-made ANKA-S drones as maritime surveillance tools over disputed waters, as part of a diversification effort that includes proposals for surface combatants and naval systems.

Contracts for three ANKAs were inked at the Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition(LIMA 2023); deliveries and basing in Labuan, an island federal territory of Malaysia, underscore Kuala Lumpur’s push to expand surveillance of the South China Sea and nearby sea lanes.

“Türkiye’s flexibility—its readiness to localise production, embed technology, and tailor packages—is what sets it apart,” Yas says, pointing to co-production and training as central to sustaining capability without eroding sovereignty.

According to Yas, Vietnam’s long-standing ‘Four Nos’—no military alliances, no siding with one power, no foreign bases, and no use or threat of force—leave little room for treaty-bound partnerships. But they do not preclude modernisation or industrial cooperation.

Turkish officials emphasised that the new Vietnam track will focus on training, defence industry links, UN peacekeeping, and exchanges in naval, air, cyber, and non-traditional security fields—areas that align with Hanoi’s non-aligned doctrine while building practical capacity.

“This is cooperation built on pragmatism and trust,” Yas says. “Both Ankara and Hanoi are middle powers intent on protecting sovereignty, building resilience, and avoiding dependency on any single great power.”

Great potential

Atli views the current wave of activity as comprising two strands that reinforce each other: multilateral outreach to ASEAN, and a denser web of country-by-country ties.

“They are not alternatives,” he says. “They are complementary pillars of a sustained presence.”

Ankara’s officials echo that narrative, casting Southeast Asia as a proving ground for Türkiye’s evolved defence economy—drones, precision weapons, warships, and now a fifth-generation jet—battle-tested from the Caucasus to North Africa.

The message in Hanoi was similar: Türkiye wants to translate its industrial rise into long-term partnerships that build local capacity and reduce single-supplier risk.

“Türkiye and Southeast Asia share a common language: both seek a more balanced international order, a more inclusive global governance system, and a world where medium powers are not reduced to pawns in superpower rivalry,” Atli says

This shared worldview strengthens the political and strategic logic of Türkiye–ASEAN ties. For relations to be sustainable, they must rest on economic foundations—and not just trade, but long-term investments. Especially relevant in light of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).”

RCEP, which brings together 15 countries including ASEAN members, China, Japan, and South Korea, constitutes the largest free trade bloc in the world.

“Türkiye is not a member, and at first glance, this seems like a disadvantage. Yet there is a “half-full” side of the glass,” Atli says.

“If a Turkish company sets up production in Vietnam, it can export tariff-free to all 15 RCEP members. Conversely, Southeast Asian firms investing in Türkiye can leverage Türkiye’s Customs Union with the EU to reach European markets.”

The road ahead

Whether this momentum hardens into a durable regional role will depend on execution: timely deliveries to Indonesia, smooth operationalisation in Malaysia, and tangible projects in Vietnam.

For now, Türkiye has placed markers on all three fronts—and in a region wary of binary choices, its offer of capability without entanglement is landing with new traction.

“Middle powers are shaping the security architecture of a multipolar Asia,” Yas tells TRT World. “If managed carefully, Türkiye’s partnerships can become a template—built not on alliances or coercion, but on mutual respect, technological pragmatism, and shared strategic autonomy.”