Algorithms have long participated in governing. They determine which job advertisements reach which citizens, which tax returns are flagged for audit, which welfare cases are prioritised, and even how police patrol routes are scheduled.

Much of this has taken place quietly, under the banner of “decision support,” rather than as overt decision-making.

What makes the recent developments in Albania and Japan distinctive is that the systems are no longer hidden infrastructure.

Albania’s government has formally tasked its digital assistant Diella with managing procurement processes, and Japan’s small Path to Rebirth party has declared it will appoint an AI as its leader.

Neither case represents the full transfer of authority to machines. Diella remains a supervised workflow tool, and the Japanese party has no seats in the national legislature and must still designate a human representative for official filings.

Even so, these moves are significant. They shift algorithmic decision-making from a backstage function into a named, publicly acknowledged institutional role.

They signal that algorithmic governance, long a quiet fact of administrative life, is becoming explicit. They must be addressed as questions of institutional design, legitimacy, and accountability.

Algorithmic governance, broadly understood, is not new. For decades, governments and firms have used scoring formulas, risk models, and decision trees to steer outcomes.

What is distinctive today is the discussion of AI systems that learn from data, adapt over time, and operate at scale.

These systems do more than execute fixed rules. They generate patterns, rank alternatives, and sometimes propose actions that were not foreseen by their designers.

This makes them powerful, but also harder to scrutinise.

The recent public appointments of AI systems in Albania and Japan draw attention to this shift. This is about governing with systems that evolve, whose reasoning must remain intelligible if democratic oversight is to be preserved.

Algorithmic governance and the dream of objectivity

From Leibniz to Condorcet, Enlightenment thinkers imagined replacing dispute with calculation.

Leibniz even proposed a “universal calculus” through which adversaries could settle disagreements by simply declaring calculemus (“let us calculate”).

Jeremy Bentham translated this vision into utilitarian policy, arguing that the aim of governance should be the maximisation of collective happiness through rational computation.

Contemporary algorithmic governance appears to bring this project to life. It promises decisions purged of whim and prejudice, delivered with the regularity of a function call.

Modern governance has long wrestled with the tension between order and autonomy, between the promise of impartial administration and the fear of suffocating control.

Max Weber’s sociology of bureaucracy offers the first major conceptual anchor. Weber described the ideal modern state as governed by rules rather than personal whim, characterised by formal procedures, written records, and hierarchical oversight.

Algorithmic systems are a logical extension of this project. They promise consistency by removing discretion at the lowest levels and enforcing uniformity.

But they also make Weber’s “iron cage” tighter. From this perspective, there is considerable historical continuity where algorithmic governance is not a rupture but an intensification of rationalisation.

Later, cybernetics, emerging in the 1940s, reframed governance as a problem of feedback control. Norbert Wiener’s insight was that biological, mechanical, or social systems could be regulated by sensing their state, comparing it to a goal, and applying corrections.

Stafford Beer’s ‘Viable System Model’ in the 1970s applied this logic to whole economies, imagining the state as a living information processor.

Algorithmic governance operationalises this vision. Sensors become digital data streams, controllers become machine learning models, and corrective actions can be applied at machine speed.

In the post-war era, governments embraced operations research, linear programming, and decision analysis to optimise logistics, budget allocations, and social planning.

Cold War analysts chased ‘optimal’ answers under tight limits.

Think RAND’s tabletop war games that let officials rehearse crises, Soviet efforts to run the economy with feedback-driven computer models, and British post-war planning that used input-output tables to set production goals.

Because the methods were legible, policymakers could see how the numbers produced the advice."

Modern algorithmic systems inherit the optimisation ethos but replace interpretable equations with opaque neural networks. This creates a historical discontinuity where we have inherited the faith in optimality without the guarantee of explainability.

The 1990s and 2000s digitisation wave focused on efficiency with online portals, electronic filing, and automated case management. These were largely service upgrades, not redefinitions of power.

Algorithmic governance uses that infrastructure as its substrate but moves from passive record-keeping to active steering.

Systems now prioritise which cases human officers see, predict which policies will hit performance targets, and sometimes auto-enforce penalties or eligibility decisions.

The state is shifting from a registry to a recommender and, in some areas, to an actor.

Governance by AI

What is novel in this moment is not the aspiration to rationalise governance but the properties of the tools now being deployed.

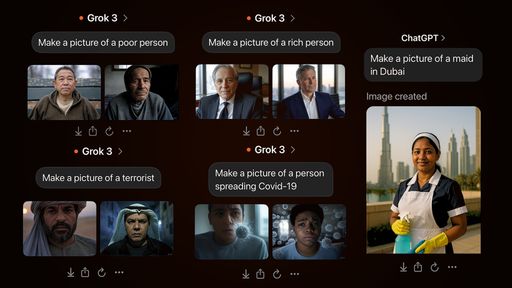

Unlike the rule-based systems of earlier decades, contemporary AI operates on statistical inference rather than explicit logic. It produces outputs not by applying transparent rules but by mapping complex correlations in data.

This allows flexibility and adaptation where systems can update themselves as new data arrives.

Yet, it also introduces opacity. Policymakers may find it difficult to explain why a given recommendation was made or to reconstruct the chain of reasoning behind an outcome.

In this sense, algorithmic governance today does not merely tighten Weber’s cage; it risks replacing visible bars with invisible ones.

Another key difference is scale and granularity. Earlier administrative systems could only generalise.

They applied uniform rules to broad classes of cases. Machine learning models, by contrast, enable micro-differentiation. Risk scores, eligibility decisions, and policy nudges can be tuned to the level of neighbourhoods or individuals.

This raises both opportunities and concerns. On one hand, resources can be targeted with unprecedented precision, potentially reducing waste and inequity.

On the other hand, such fine-grained governance can fragment the very idea of a public, replacing collective treatment with individualised optimisation and making political justification harder: why was my case treated differently from my neighbour’s if no human ever decided?

There is also a temporal shift. Classic bureaucratic and planning systems were periodic and retrospective. Census data every decade, budgets every fiscal year, policy revisions every legislative session.

Modern AI systems can function continuously, ingest real-time data and adjust decisions on the fly.

This introduces the possibility of dynamic governance, which would be a kind of rolling administration that is always slightly in flux.

However, this complicates oversight. When decisions are constantly updated, what exactly is being evaluated in a legislative audit or judicial review? Last month’s model version, last week’s, or the one running this morning?

AI-led governance introduces a new distribution of agency. Today’s systems can generate options and propose strategies unforeseen by their designers.

This blurs the line between decision support and decision-making. It also shifts the skill set required of public officials. They must now govern not only populations but models.

They must learn when to trust, when to override, and how to translate public values into technical parameters.

The question now is whether the AI model keeps learning in a way consistent with democratic intent.

Early case studies

Algorithmic systems differ from earlier administrative technologies in three important ways. They are adaptive, they rely on probabilistic inference rather than fixed rules, and they operate at a scale that can affect millions of cases simultaneously.

These properties allow governments to target resources with unprecedented precision and anticipate problems before they escalate.

They also magnify the impact of mistakes, embed biases in ways that may be hard to detect, and make oversight more complex.

Rather than dismissing these developments as publicity stunts or fearing them as harbingers of machine rule, we should treat Albanian and Japanese experiments as early case studies.

They offer a chance to design the norms, audit practices, and legal frameworks that will govern algorithmic decision-making before it becomes deeply entrenched.

Albania and Japan have, intentionally or not, made algorithmic governance visible.

The task now is to decide how to keep it legitimate, contestable, and consistent with democratic principles before the next office gets a digital nameplate.