China and the 11-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) recently upgraded their free trade agreement amid renewed turbulence in Beijing’s relations with the Trump administration.

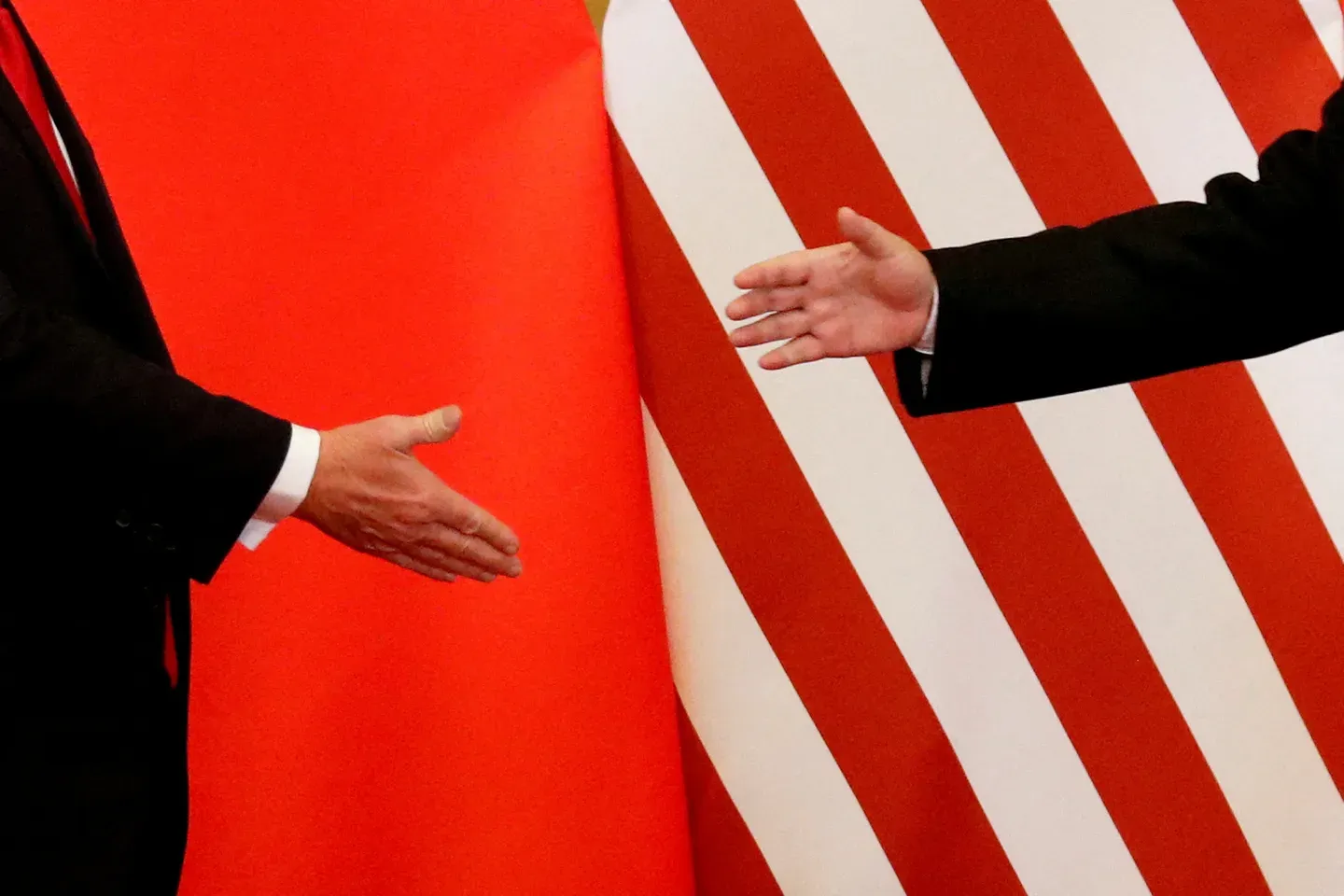

Before a recent meeting between President Donald Trump and Xi Jinping, both sides exchanged new threats over tariffs and rare materials.

Yet they now anticipate progress on export controls, rare earth minerals and tariff reductions as Trump’s latest announcements reignite global debate over economic power, supply chains, and the next phase of strategic rivalry.

GDP and export figures are treated as proxies for global destiny, as if the fate of the world order could be reduced to spreadsheets.

Yet this fixation on tariffs and grand strategy misses a deeper truth: the real contest between the US and China will not be decided by trade or technology—but by societies themselves.

For decades, global competition has been framed through two main paradigms: the Washington Consensus of market liberalism and the Beijing Consensus of state-led growth.

But it is time to move beyond this binary and imagine what a decolonial perspective envisions for humanity—a pluriversal world order that rejects all forms of colonial expansion, the deepening inequality and environmental destruction of current development models to reach social harmony, and the creeping re-colonisation visible in the Israelisation of the global order or the warfare-state logic of a Moscow Consensus in where social reluctance is clear.

Despite such urgent critiques, debates over great power rivalry remain confined to the same abstractions—who gains, who declines, and who writes the rules.

What this framework overlooks is simple yet decisive: power endures not through economies or expansionist policies alone, but through the societies that sustain them.

It is social cohesion, moral legitimacy, and institutional adaptability—not merely armies or GDP—that determine who survives and who collapses.

Beyond power politics and Europe’s supremacy

History shows this clearly. The rise and fall of empires have always depended not only on external pressures but also, and more importantly, on internal dynamics.

Nineteenth-century non-Western development strategies began with a strong emphasis on military modernisation, yet they soon expanded to include profound social reforms across the Ottoman Empire (and later Türkiye), China, Russia, and Iran.

Even decolonisation was not simply anti-Western; it was shaped by the Westernisation path for development itself.

The West long provided the model for both state and society in the modern era. Yet today, this example is no longer uncontested.

The most pressing challenges are not only geopolitical but also social. Polarisation, inequality, migration, demographic decline, loneliness, and crises of legitimacy shake Western societies from Europe to the US, and even in Westernised non-Western contexts.

Critical and local approaches, as highlighted by decolonial thinkers like Walter Mignolo, challenge the universality and epistemic supremacy of Western sociology and propose alternative frameworks rooted in local histories.

Great power competition cannot be grasped solely through military or economic lenses—it must also reckon with these social fractures in the West and the rise of local narratives and civilizational discourses elsewhere.

The US’s crisis, China’s question

Consider the US. By economic, military, and political measures, it still stands as the world’s preeminent power.

Yet its greatest adversary may be internal. From rising drug abuse and gun violence to bitter culture wars, the US’s domestic fractures expose vulnerabilities more profound than any external challenge.

Once a country that projected liberal values, the American Dream, and religious and ideological ecumenism, the US now faces crises of legitimacy at home and credibility abroad.

Its complicity in humanitarian catastrophes, such as the genocide in Gaza, further erodes its moral authority.

China, on the other hand, presents a different picture. Crime and homelessness are low, vices like drugs and gambling are tightly suppressed, cities are secure, and the state appears socially functional.

The Chinese model of governance is built on total obedience of its citizens, which gives Beijing a remarkable capacity to mobilise. But it also exposes its own weaknesses.

The one-child policy illustrates both sides: initially a sweeping social and economic success through birthrate control, it left behind demographic decline, weakened family ties, and growing social atomisation, undermining China’s long-term strength.

This functional and powerful state system has limitations to change the story in ordinary life to increase the birthrate.

As the Harvard emeritus professor on China studies, Martin K. Whyte warned of population decline in his article, “be careful what you wish for.”

A society that follows can achieve rapid change, but uncritical compliance may carry unintended consequences that unfold over the long term, beyond the gains of a single generation.

At the same time, China defines itself not merely as a state but as a civilisation, alongside its revolutionary Marxist ideas.

It has long absorbed outside influences into its historical and contemporary narratives, treating the Mongols as the Yuan dynasty rather than barbarians, and incorporating Muslim communities from its earliest encounters with Islam in Chinese civilisation, which also attracts critics against the concepts of Islam in Chinese characteristics.

This inclusive historiography gives China resilience and continuity.

Yet the question remains: can such a civilisation project an ecumenical vision fit for a global order, or will it remain a bounded national narrative?

In an interconnected world, power is not secured by territory alone—it requires an idea that can connect with others, address migration, and engage with rising populations in Africa and beyond.

The Soviet lesson for tomorrow

The Soviet Union offers a cautionary tale. It did not collapse because of military weakness but because of social failure. A society that no longer believed in its own vision could not endure.

The lesson is clear: power is not just about data, weaponry, or economic output. It is about the social realities that make power sustainable.

Great power competition, then, is not simply about global politics. It is also a sociological one.

States may compete on the global stage, but societies decide their fate. To understand the future of world order, we must look not only at geopolitics but also at the deeper social currents that shape the destinies of nations.