The traditional healer was dying. So were his patients. In western Kenya, entire villages were burying their dead, convinced that one family – the only household probably still healthy – had cursed them all with witchcraft.

Then a chief who had seen sleeping sickness before spoke up. Get to a health facility, he advised. This isn't sorcery. It's a disease.

Twenty-five years later, Salome Bukachi can finally exhale. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recently certified Kenya free of human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness, a disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei that spreads to humans and even cattle through the bite of infected tsetse flies.

Bukachi, professor of medical anthropology at the University of Nairobi, had spent her entire career fighting this disease. Now, the WHO certificate confirms what years of surveillance have shown: the parasites are gone.

"It's a major feat because it entailed years of coordinated surveillance," Bukachi tells TRT Afrika, recounting her years in the field testing people and animals, checking tsetse flies and monitoring six endemic sites across the country over and over. "Elimination means that we no longer have transmission of the disease in humans."

Bukachi attributes this success to the communities living in six historically endemic sites and the medical teams and scientists who relentlessly worked to rid the region of the scourge.

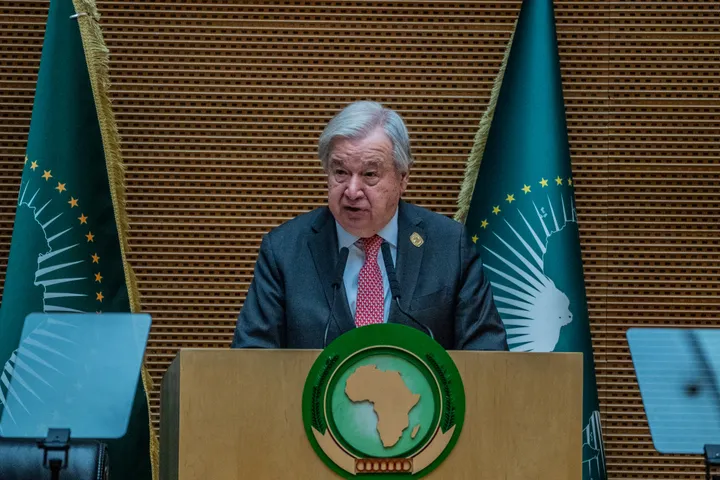

WHO's director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said as much in his official statement. "I congratulate the government and people of Kenya on this landmark achievement. Kenya joins the growing ranks of countries freeing their populations of human African trypanosomiasis. This is another step towards making Africa free of neglected tropical diseases."

Mystery trail

At the Kenya Trypanosomiasis Research Institute, which merged with the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute in 2003, Bukachi studied communities where sleeping sickness had taken hold.

“I did my study in the western part of Kenya and there were villages where there was a death almost in every homestead,” she says.

“They were thinking that, one of the members in the village had bewitched the rest of the members because everyone was falling sick apart from one household.”

Things would get worse when even the traditional healer couldn't solve the riddle, much less cure himself.

"For a while, they didn't know what was happening until, a chief who had been involved in a previous sleeping sickness campaign came and told them that this wasn't witchcraft," recalls Bukachi.

Confusing symptoms

Sleeping sickness is known to make many patients incoherent and confused. Often, these symptoms mimic mental illness. Once the parasites reach the brain, sleep patterns flip.

"When one is meant to be sleeping, the person is awake," Bukachi explains. "Sometimes the person could just be having a conversation and suddenly dozes off. You could even be eating and go to sleep without warning, maybe just as you are about to take a bite of your ugali."

The parasites cross what scientists refer to as the blood-brain barrier. They multiply. The brain can no longer cope, resulting in rapidly diminishing cognitive function.

"That's when the patient starts behaving and sleeping abnormally," Bukachi tells TRT Afrika.

What adds to the confusion is that early symptoms of sleeping sickness look like malaria – fever, headache, joint pain, appetite changes and weight loss. Then it gets worse.

"There is one very acute variant that is common in the East African region. We call it Rhodesiense sleeping sickness (r-HAT)," explains Bukachi, noting that without treatment, the infection can turn fatal within weeks.

"The other one, dominant in the West African region (gambiense), is more chronic. Here, the symptoms take time to become full-blown."

Treatment protocol

Until a few decades ago, treatment for sleeping sickness was so harsh that many patients wouldn't be able to tolerate it.

"You wouldn't want to get sleeping sickness around the 1990s," says Bukachi. "A patient with late-stage disease would spend almost a month in hospital."

Adverse reactions to standard drugs were common, requiring close medical supervision. Before letting a patient without symptoms leave the hospital, doctors needed to make sure the person was "clean", which entailed a painful procedure called a lumbar puncture.

"They would press a long needle at the base of your spine to draw fluid and test it for parasites. If they found none, then you were okay; you could now go home," Bukachi tells TRT Afrika.

Kenya's HAT history

The first cases of HAT in Kenya were detected in the early 20th century. The last two patients, both infected in the Masai Mara National Reserve, were diagnosed in 2012.

Kenya joins Benin, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Rwanda, Togo and Uganda in the list of African countries to have eliminated the deadly disease.

"This achievement will not only protect our people but also pave the way for renewed economic growth and prosperity," says Aden Duale, Kenya's cabinet secretary for health. "It's the culmination of many years of dedication, hard work and collaboration."

As with most other diseases, early diagnosis improves health outcomes massively among patients suffering from sleeping sickness.

"We use what we call the one-health approach, combining the environment, the human and the animal," says Bukachi.

This means treating livestock, clearing bushes around homes and using insecticide-treated nets and traps or targets.

While tsetse flies still exist in the endemic sites, many years of sustained treatment and prevention campaigns have cleared the environment of the trypanosome parasite that causes the disease.

"A coordinated effort by different disciplines, departments and research institutions has enabled us to deal with this," Bukachi tells TRT Afrika. "If Kenya managed to achieve this, other countries too can."