Landlocked nations in Eastern Africa are scrambling for better access to seaports, with frustrations over border bureaucracy and transport costs boiling over into increasingly blunt outbursts from the affected parties.

President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda went to the extent of issuing a strong warning to neighbouring Kenya before later moderating his remarks last month. Although temporary, the brinkmanship reflected longstanding frustrations over Uganda's access to the Indian Ocean.

"My sea is the Indian Ocean," he declared at a media briefing, comparing the situation to a block of flats where residents on the upper floors have equal rights to the garden below as those on the ground floor.

To the north, Ethiopia's development boom, which includes Africa's largest hydroelectric dam and the continent's largest airport project, is seemingly constrained by lack of access to the sea.

Its primary import gateway is a Red Sea port in neighbouring Djibouti, which charges millions of dollars a year in port fees, according to officials.

Ethiopian firms incur an additional US $1 billion annually in inland transportation costs.

With a population exceeding 100 million, Ethiopia is the world's most populous landlocked country. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has made clear his determination to regain access to the Red Sea, which Ethiopia lost when Eritrea seceded in 1993. His government insists it wants to gain sea access peacefully.

Experts blame the rising unease over seaport access on diplomatic failures and constraints facing regional blocs that were formed to oversee economic integration. They point to gaps between principles outlined in regional treaties and administrative procedures implemented by state bureaucrats.

"What is on paper and in practice are two different things. When it comes to implementation, either partial implementation or personal interests come in. This is an issue affecting so many landlocked countries of the region," Prof David Mugisha, a Ugandan scholar in international relations, tells TRT Afrika.

Varying priorities

While Ethiopia's concerns centre on high trade costs and access to world markets, Uganda considers dependence on the politics and policies of its neighbours a vulnerability that it must eliminate from the equation.

Uganda is linked to the Indian Ocean through transport corridors that run across Kenya and Tanzania, connecting to the Mombasa and Dar es Salaam ports, respectively.

A proposed crude oil pipeline running from oilfields in northern and western Uganda to the Kenyan port of Lamu fell through in 2016 after President Museveni opted for a shorter route through Tanzania to the Tanga port.

The country's proven oil reserves currently stand at around 6.6 billion barrels, with 1.6 billion barrels being economically feasible for extraction based on data from the energy ministry. Oil production is expected to start next year, which explains why Kampala's tone has become increasingly assertive on regional matters that will potentially have a bearing on the sector.

President Museveni spoke last month about the need for joint defence planning among the three neighbours to protect the coastline, which he emphasised was a collective asset rather than a national possession.

"There is the issue of strategic security. Even if we are together in the East African Community (EAC), we don't plan defence together. That is why I was talking of political federation; the idea is for us to maximise our potential," he said.

As someone who has been in office for nearly 40 years, Museveni has had to contend with the differing perspectives of five Tanzanian and four Kenyan presidents alongside the instability that accompanied elections in Kenya in 2007 and the recent polls in Tanzania.

Analysts argue that the Ugandan President is seeking guarantees on access to the Indian Ocean to shield the country from changes of leadership in neighbouring countries.

"I think diplomacy has done its part, and a lot has been achieved, but the pace at which things are moving and, given that Museveni has been in power 40 years, I think there is only so much somebody can take. So, he is not speaking out of aggression, but a long trail of frustrations," says Prof Mugisha.

Ethiopian port of call

Ethiopia sits less than 80km from the Red Sea but is blocked by a strip of Eritrean territory.

Asmara has accused its landlocked neighbour of planning to seize its port at Assab, although Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed denies planning any act of aggression to gain access to the sea. Ahmed describes the question of Red Sea access as "an existential issue".

The two countries had a historic rapprochement, for which Abiy won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019. But they have since fallen out.

Ethiopia's attempt in January 2024 to lease a 20km stretch of coastline in Somalia's breakaway Somaliland region sparked a diplomatic impasse, with Mogadishu accusing Ethiopia of undermining its territorial integrity.

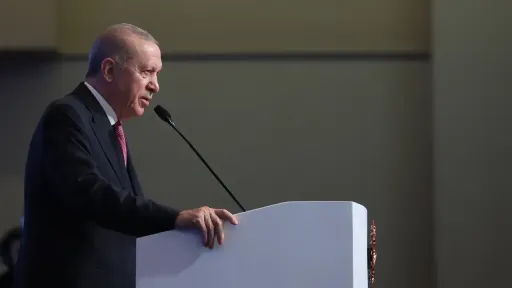

Turkish mediation efforts laid the groundwork for rapprochement between the two neighbours, leading to the landmark Ankara Declaration in which Prime Minister Abiy and President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud of Somalia agreed to respect each other's sovereignty.

However, Abiy has continued to express aspirations for a seaport. He told Ethiopian lawmakers in October that he was "a million percent sure" Ethiopia wouldn't remain landlocked, "whether anyone likes it or not".